Just Another Day At The Office

If You're A Gurkha Soldier, Maybe ...

On Wednesday, June 1, 2011 a handsome young man with a nut-brown complexion stepped into the inner sanctum of Buckingham Palace and into a mob of photographers. Resplendent in his scarlet-piped pillbox cap and black-ink tunic, he flashed a rare, self-conscious smile, and held up a gift from ’Er Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Cameras flashed; voices respectfully murmured. Jaded journalists made no jokes or jibes. Simple, unaffected heroism sometimes has that effect.

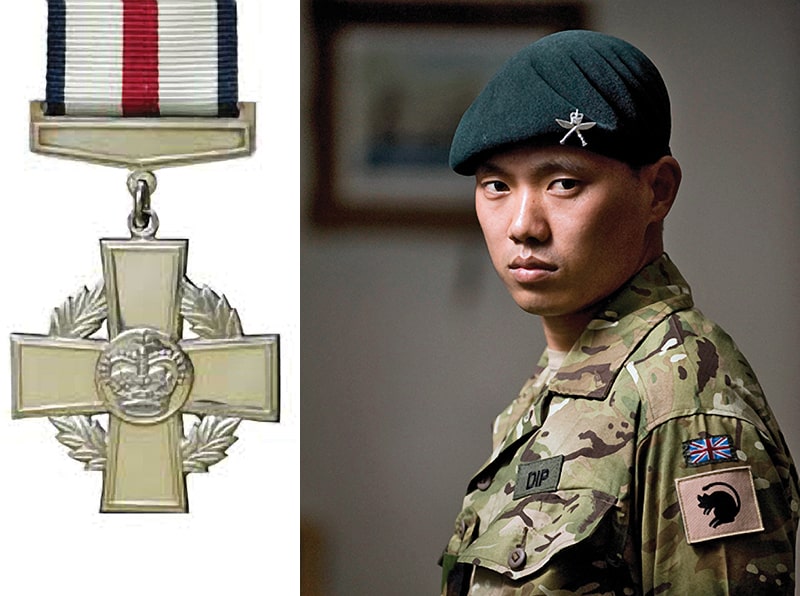

Sergeant Dipprasad Pun, of the Royal Gurkha Regiment, had just been “gonged” by the Queen: awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross, Britain’s second-highest decoration for bravery in combat. It is unknown how many generations of “Sergeant Dip’s” family have served in Gurkha regiments, but he knows he represents the third generation of his immediate family to have been highly decorated for valor. With a modesty typical of Gurkhas, he felt his actions were all in a day’s work; doing one’s duty.

Meantime, at a barracks in Kent, another young Gurkha was keeping a low profile, somewhat confused about being “notorious” to the outside world and “an embarrassment” to British diplomats. His fellow Gurkhas were equally nonplussed. He had only done his duty.

In India, a Gurkha sergeant who had been “RIF’d” into early retirement was back at work with a promotion, three new decorations and a 50,000-rupee award in his bank account, wondering what all the fuss was about. He saw his duty, and simply did it.

“I was definitely going to die, so…”

Dip’s unit, a platoon from the 1st Battalion of the Royal Gurkha Regiment, operated from a remote outpost in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. Sited in an area thick with Taliban, the unit’s prime duties included aggressive patrolling, and manning a critical checkpoint on the road east of a small village. The outpost had been attacked several times. One evening, the then-Corporal Dip was one of four Gurkhas left at the base while the rest of the platoon pushed out on patrol.

Dip was alone at the checkpoint, an elevated structure in the center of the compound, when just after dark, he heard noises. Investigating, he found Taliban planting an IED in front of the gate. Dip grabbed two radios, his SA80 rifle, and a GPMG—General Purpose Machine Gun. As the Taliban moved into assault position, Dip advised his commander by radio that the outpost was under attack, fired a grenade, and kicked off the firefight. His three comrades were pinned down inside and couldn’t respond.

Under attack on three sides by 15 to 30 Taliban, he kept moving, emptying all six mags from his SA80, launching 17 grenades and firing 250 GPMG rounds. Some fell, but others kept coming, and trying to scale the wall. Screaming, “Marchi talai!” (I will kill you!) in Nepalese, he hammered one down like a nail with the GPMG tripod, and swept another off the wall with a sandbag. When the survivors regrouped, Dip triggered a claymore mine blast. They fled, leaving three bodies behind.

Taking out a skeleton-staffed outpost should have been a slam-dunk. Instead, the Taliban got slammed and dunked.

Afterward, he explained, “I thought I was definitely going to die so I thought I’d kill as many of them as I could before they killed me.” Just another day at the office.

One Head And 40 Bandits

Another Gurkha unit from 1st Battalion was tasked with hunting down a certain Taliban warlord. The orders were to positively identify their target. They found him, surrounded by his pals, and in a ferocious firefight, he was killed. Still under heavy fire, they could not carry the body away. One Gurkha drew his kukri knife and removed the warlord’s head. They fought their way back out. He was positively ID’ed.

The diplomatic community went nuts. The Gurkhas simply couldn’t comprehend the problem. Absent orders to the contrary, they did what they had done in countless past conflicts, often times commanded to bring back proof of important kills. Citing “international embarrassment,” the young Gurkha was sent back to the barracks in Kent.

Rolling through jungled country in West Bengal, India, several passengers of a train suddenly revealed themselves as bandits; seizing control and stopping the train to let waiting bandits aboard. There were 40 of them, armed with pistols, swords and knives. Loud and threatening, they stripped passengers of money, jewelry and other valuables. One passenger, Bishnu Shresthra, sat calmly and watched.

Faced with a cutback in personnel, Sergeant Shresthra had voluntarily taken early retirement from his Gurkha regiment in the Indian Army to save the billet for a younger Gurkha.

He didn’t make a move until bandits grabbed an 18-year-old girl and threatened to rape her in front of her parents. That’s when he stood, drew the long, curved, ever-present kukri concealed at his side—and attacked. Conditions were perfect for a Gurkha’s hacking and slashing fighting style with the kukri: in the train’s narrow passageway, only two or three bandits at a time could face him. And the odds were on his side: just 40 dacoits against a veteran Gurkha! The fight raged on for 20 minutes.

Shreshthra suffered knife wounds to his hand and arm, later requiring extensive surgery. He killed three dacoits, seriously wounded eight, and literally chased the others off the train and into the jungle—alone. Police recovered 400,000 rupees, 40 gold necklaces, 40 laptops and 200 cell phones dropped by the fleeing bandits. He did not boast of his actions. The girl told police what he had done. He explained that fighting enemies in battle was his duty as a soldier. Fighting the dacoits, he said, was “my duty as a human being.”

The Indian government invited Shresthra to rejoin his regiment.

The Gurkhas: Asia’s Spartans

Unfortunately, we’ve no space here to tell the long, distinguished history of Nepal’s Gurkha warriors, who have been “contract soldiers” of the British Army since the early 1800s, and of the Indian Army since independence. If you don’t know it, you’ll enjoy researching it.

I first saw a Gurkha as a boy in the Pacific. My father had described them as some of the world’s bravest, most honorable soldiers. “But he’s hardly bigger’n me!” I observed.

“In battle,” dad said, “That man is about 9′ tall.”

Ayo Gorkhali!

Connor OUT